Here is a view of the flight track of the second mission, in which we studied an easterly wave moving to the west when it was located to the south of St. Croix and Puerto Rico. We dropped 23 dropsondes on this flight. Shown in the background is a false color image of the convection (major blowup!) associated with this wave. Overshooting convective tops (see the righthand picture below) were well above our altitude of 45,000 feet!

St. Croix gets frequent intrusions of air laden with dust from Africa's Sahara desert and the Sahel arid region to the south. These are lifted into the atmosphere by strong outflows from thunderstorms further south over Africa. Below one can see the difference between air from the Saharan air layer and more pristine air. The view is from the breakfast terrace of the Buccaneer hotel.

In mission 9 we flew an easterly wave which the National Hurricane Center briefly classified as tropical storm Gaston. The flight pattern is shown below, along with a swirl of clouds in the low-level stratus. This was probably the site of a major convective blowup on the previous day which led to the designation as a tropical storm. The location of the swirl is noted in magenta on the map.

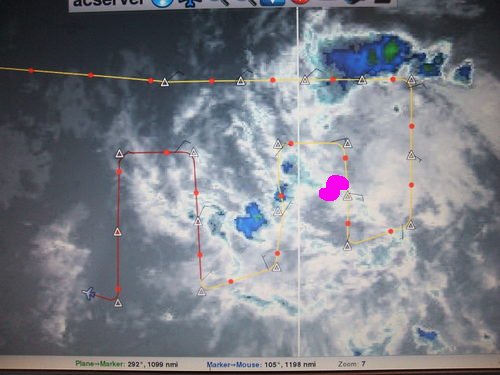

Here is the main deep convection in Gaston a few days later in mission 11 as well as a view of our flight pattern from the on board display:

Air spiraling into the center around the east and north sides of Gaston, as seen above right, became moister and more convective with time, as shown below:

Gaston succumbed to encroaching dry air and never recovered its original, brief glory, which was actually a good thing, as it passed almost directly over St. Croix! It will make an excellent case study of tropical non-cyclogenesis.

The system we called PGI44 formed off the northeast coast of South America and moved directly south of St. Croix as a strong tropical wave. This system presented some unique problems as its northern edge affected St. Croix, as seen from the G-V just before takeoff (below left). As the flight path shown below right suggests, Venezuela would not let us into their airspace at the last minute, which resulted in some creative flight pattern design!

As shown below in pictures from the G-V, this was a strong system with widespread convection and overshooting tops. But it was developing very slowly. Would it become a tropical cyclone? Stay tuned!

Here is an infrared picture of PGI44 as it approaches the Yucatan Peninsula. The red dashed line shows its projected track.

Postscript on PGI44: At 2100 UTC on 14 September PGI44 was elevated from a "region of interest" to tropical storm Karl by the National Hurricane Center. It produced 55 kt winds before going ashore on the Yucatan peninsula. Though not so good for the people of Chetumal, Mexico, those of us tracking and flying this system for the previous week took great satisfaction in this turn of events -- not the least of whom was Carlos, who was on the G-V returning to St. Croix from a nine-hour flight into PGI44/Karl when this declaration was made. We noted immediately that Karl is the German version of Carlos! The formation of Karl may be the best documented instance ever of tropical cyclogenesis.

A sad note: After passing over the Yucatan Peninsula, Karl intensified into a major hurricane, reaching category 3 before smashing into the Mexican coast just north of the city of Veracruz. Several people were killed, offshore oil rigs were shut down, and serious damage was done by the hurricane in the Mexican state of Veracruz. NASA and NOAA continued to fly research missions into Karl after it emerged from the Yucatan into the Gulf of Campeche.

PREDICT isn't the only New Mexico science going on in St. Croix. Below is an antenna for the Very Long Baseline Array radio telescope, which is based at the National Radio Astronomy Observatory building on the NM Tech campus.